Third party (U.S. politics)

Third party, or minor party, is a term used in the United States' two-party system for political parties other than the Republican and Democratic parties.

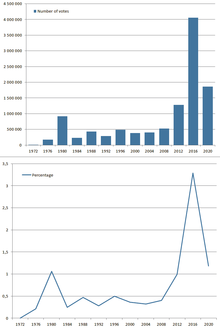

Third parties are most often encountered in presidential nominations. Third party vote splitting exceeded a president's margin of victory in three elections: 1844, 2000, and 2016. No third-party candidate has won the presidency since the Republican Party became the second major party in 1856. Since then a third-party candidate won states in five elections: 1892, 1912, 1924, 1948, and 1968. 1992 was the last time a third-party candidate won over 5% of the vote and placed second in any state.[1]

Competitiveness

[edit]With few exceptions,[2] the U.S. system has two major parties which have won, on average, 98% of all state and federal seats.[3] There have only been a few rare elections where a minor party was competitive with the major parties, occasionally replacing one of the major parties in the 19th century.[4][5] The winner take all system for presidential elections and the single-seat plurality voting system for Congressional elections have over time helped establish the two-party system (see Duverger's law). Although third-party candidates rarely win elections, they can have an effect on them through vote splitting and other impacts.

Notable exceptions

[edit]Greens, Libertarians, and others have elected state legislators and local officials. The Socialist Party elected hundreds of local officials in 169 cities in 33 states by 1912, including Milwaukee, Wisconsin; New Haven, Connecticut; Reading, Pennsylvania; and Schenectady, New York.[6] There have been governors elected as independents, and from such parties as Progressive, Reform, Farmer-Labor, Populist, and Prohibition. After losing a Republican primary in 2010, Bill Walker of Alaska won a single term in 2014 as an independent by joining forces with the Democratic nominee. In 1998, wrestler Jesse Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota on the Reform Party ticket.[7]

Sometimes a national officeholder that is not a member of any party is elected. Previously, Senator Lisa Murkowski won re-election in 2010 as a write-in candidate after losing the Republican primary to a Tea party candidate, and Senator Joe Lieberman ran and won reelection to the Senate as an "Independent Democrat" in 2006 after losing the Democratic primary.[8][9] As of 2024, there are only four U.S. senators, Angus King, Bernie Sanders, Kyrsten Sinema, and Joe Manchin, who identify as Independent and all caucus with the Democrats.[10]

The last time a third-party candidate carried any states in a presidential race was George Wallace in 1968, while the last third-party candidate to finish runner-up or greater was former president Teddy Roosevelt's 2nd-place finish on the Bull Moose Party ticket in 1912.[1] The only three U.S. presidents without a major party affiliation upon election were George Washington, John Tyler, and Andrew Johnson, and only Washington served his entire tenure as an independent. Neither of the other two were ever elected president in their own right, both being vice presidents who ascended to office upon the death of the president, and both became independents because they were unpopular with their parties. John Tyler was elected on the Whig ticket in 1840 with William Henry Harrison, but was expelled by his own party. Johnson was the running mate for Abraham Lincoln, who was reelected on the National Union ticket in 1864; it was a temporary name for the Republican Party.

More favorable electoral systems for third parties

[edit]Electoral fusion

[edit]| Part of the Politics series |

| Voting |

|---|

|

|

Electoral fusion in the United States is an arrangement where two or more United States political parties on a ballot list the same candidate,[11] allowing that candidate to receive votes on multiple party lines in the same election.[12]

Electoral fusion is also known as fusion voting, cross endorsement, multiple party nomination, multi-party nomination, plural nomination, and ballot freedom.[13][14]

Electoral fusion was once widespread in the U.S. and legal in every state. However, as of 2024, it remains legal and common only in New York and Connecticut.[15][16][17]Ranked-choice voting

[edit]

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) can refer to one of several ranked voting methods used in some cities and states in the United States. The term is not strictly defined, but most often refers to instant-runoff voting (IRV) or single transferable vote (STV), the main difference being whether only one winner or multiple winners are elected.

At the federal and state level, instant runoff voting is used for congressional and presidential elections in Maine; state, congressional, and presidential general elections in Alaska; and special congressional elections in Hawaii. Starting in 2025, it will also be used for all elections in the District of Columbia.

As of February 2024, RCV is used for local elections in 45 US cities including Salt Lake City and Seattle.[19] It has also been used by some state political parties in party-run primaries and nominating conventions.[20][21][22] As a contingency in the case of a runoff election, ranked ballots are used by overseas voters in six states.[19]

Since 2020, voters in seven states have rejected ballot initiatives that would have implemented, or allowed legislatures to implement, ranked choice voting. Ranked choice voting has also been banned in eleven states.Approval voting

[edit]

Proportional representation

[edit]| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body.[23] The concept applies mainly to political divisions (political parties) among voters. The essence of such systems is that all votes cast – or almost all votes cast – contribute to the result and are effectively used to help elect someone. Under other election systems, a bare plurality or a scant majority are all that are used to elect candidates. PR systems provide balanced representation to different factions, reflecting how votes are cast.

In the context of voting systems, PR means that each representative in an assembly is elected by a roughly equal number of voters. In the common case of electoral systems that only allow a choice of parties, the seats are allocated in proportion to the vote tally or vote share each party receives.

The term proportional representation may be used to mean fair representation by population as applied to states, regions, etc. However, representation being proportional with respect solely to population size is not considered to make an electoral system "proportional" the way the term is usually used. For example, the US House of Representatives has 435 members, who each represent a roughly equal number of people; each state is allocated a number of members in accordance with its population size (aside from a minimum single seat that even the smallest state receives), thus producing equal representation by population. But members of the House are elected in single-member districts generally through first-past-the-post elections: a single-winner contest does not produce proportional representation as it has only one winner. Conversely, the representation achieved under PR electoral systems is typically proportional to a district's population size (seats per set amount of population), votes cast (votes per winner), and party vote share (in party-based systems such as party-list PR). The European Parliament gives each member state a number of seats roughly based on its population size (see degressive proportionality) and in each member state, the election must also be held using a PR system (with proportional results based on vote share).

The most widely used families of PR electoral systems are party-list PR, used in 85 countries;[24] mixed-member PR (MMP), used in 7 countries;[25] and the single transferable vote (STV), used in Ireland,[26] Malta, the Australian Senate, and Indian Rajya Sabha.[27][28] Proportional representation systems are used at all levels of government and are also used for elections to non-governmental bodies, such as corporate boards.

All PR systems require multi-member election contests, meaning votes are pooled to elect multiple representatives at once. Pooling may be done in various multi-member voting districts (in STV and most list-PR systems) or in single countrywide – a so called at-large – district (in only a few list-PR systems). A country-wide pooling of votes to elect more than a hundred members is used in Angola, for example. Where PR is desired at the municipal level, a city-wide at-large districting is sometimes used, to allow as large a district magnitude as possible.

For large districts, party-list PR is often used, but even when list PR is used, districts sometimes contain fewer than 40 or 50 members.[29] STV, a candidate-based PR system, has only rarely been used to elect more than 21 in a single contest.[a] Some PR systems use at-large pooling or regional pooling in conjunction with single-member districts (such as the New Zealand MMP and the Scottish additional member system). Other PR systems use at-large pooling in conjunction with multi-member districts (Scandinavian countries).

Pooling is used to allocate leveling seats (top-up) to compensate for the disproportional results produced in single-member districts using FPTP or to increase the fairness produced in multi-member districts using list PR. PR systems that achieve the highest levels of proportionality tend to use as general pooling as possible (typically country-wide) or districts with large numbers of seats.

Due to various factors, perfect proportionality is rarely achieved under PR systems. The use of electoral thresholds (in list PR or MMP), small districts with few seats in each (in STV or list PR), or the absence or insufficient number of leveling seats (in list PR, MMP or AMS) may produce disproportionality. Other sources are electoral tactics that may be used in certain systems, such as party splitting in some MMP systems. Nonetheless, PR systems approximate proportionality much better than other systems[30] and are more resistant to gerrymandering and other forms of manipulation.Barriers to third party success

[edit]

Winner-take-all vs. proportional representation

[edit]In winner-take-all (or plurality voting), the candidate with the largest number of votes wins, even if the margin of victory is extremely narrow or the proportion of votes received is not a majority. Unlike in proportional representation, runners-up do not gain representation in a first-past-the-post system. In the United States, systems of proportional representation are uncommon, especially above the local level and are entirely absent at the national level (even though states like Maine have introduced systems like ranked-choice voting, which ensures that the voice of third party voters is heard in case none of the candidates receives a majority of preferences).[31] In Presidential elections, the majority requirement of the Electoral College, and the Constitutional provision for the House of Representatives to decide the election if no candidate receives a majority, serves as a further disincentive to third party candidacies.

In the United States, if an interest group is at odds with its traditional party, it has the option of running sympathetic candidates in primaries. Candidates failing in the primary may form or join a third party. Because of the difficulties third parties face in gaining any representation, third parties tend to exist to promote a specific issue or personality. Often, the intent is to force national public attention on such an issue. Then, one or both of the major parties may rise to commit for or against the matter at hand, or at least weigh in. H. Ross Perot eventually founded a third party, the Reform Party, to support his 1996 campaign. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt made a spirited run for the presidency on the Progressive Party ticket, but he never made any efforts to help Progressive congressional candidates in 1914, and in the 1916 election, he supported the Republicans.

Micah Sifry argues that despite years of discontentment with the two major parties in the United States, third parties should try to arise organically at the local level in places where ranked-choice voting and other more democratic systems can build momentum, rather than starting with the presidency, a proposition incredibly unlikely to succeed.[32]

Spoiler effect

[edit]Strategic voting often leads to a third-party that underperforms its poll numbers with voters wanting to make sure their vote helps determine the winner. In response, some third-party candidates express ambivalence about which major party they prefer and their possible role as spoiler[33] or deny the possibility.[34] The US presidential elections most consistently cited as having been spoiled by third-party candidates are 1844, 2000, and 2016.[35][36][37][38][39][40] This phenomenon becomes more controversial when a third-party candidate receives help from supporters of another candidate hoping they play a spoiler role.[41][42][43]

Ballot access laws

[edit]Nationally, ballot access laws require candidates to pay registration fees and provide signatures if a party has not garnered a certain percentage of votes in previous elections.[44] In recent presidential elections, Ross Perot appeared on all 50 state ballots as an independent in 1992 and the candidate of the Reform Party in 1996. Perot, a billionaire, was able to provide significant funds for his campaigns. Patrick Buchanan appeared on all 50 state ballots in the 2000 election, largely on the basis of Perot's performance as the Reform Party's candidate four years prior. The Libertarian Party has appeared on the ballot in at least 46 states in every election since 1980, except for 1984 when David Bergland gained access in only 36 states. In 1980, 1992, 1996, 2016, and 2020 the party made the ballot in all 50 states and D.C. The Green Party gained access to 44 state ballots in 2000 but only 27 in 2004. The Constitution Party appeared on 42 state ballots in 2004. Ralph Nader, running as an independent in 2004, appeared on 34 state ballots. In 2008, Nader appeared on 45 state ballots and the D.C. ballot.

Debate rules

[edit]

Presidential debates between the nominees of the two major parties first occurred in 1960, then after three cycles without debates, resumed in 1976. Third party or independent candidates have been in debates in only two cycles. Ronald Reagan and John Anderson debated in 1980, but incumbent President Carter refused to appear with Anderson, and Anderson was excluded from the subsequent debate between Reagan and Carter. Independent Ross Perot was included in all three of the debates with Republican George H. W. Bush and Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992, largely at the behest of the Bush campaign.[citation needed] His participation helped Perot climb from 7% before the debates to 19% on Election Day.[45][46]

Perot did not participate in the 1996 debates.[47] In 2000, revised debate access rules made it even harder for third-party candidates to gain access by stipulating that, besides being on enough state ballots to win an Electoral College majority, debate participants must clear 15% in pre-debate opinion polls.[48] This rule has been in effect since 2000.[49][50][51][52][53] The 15% criterion, had it been in place, would have prevented Anderson and Perot from participating in the debates in which they appeared. Debates in other state and federal elections often exclude independent and third-party candidates, and the Supreme Court has upheld this practice in several cases. The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) is a private company.[48]

The Free & Equal Elections Foundation hosts various debates and forums with third-party candidates during presidential elections.

Major parties adopt third-party platforms

[edit]They can draw attention to issues that may be ignored by the majority parties. If such an issue finds acceptance with the voters, one or more of the major parties may adopt the issue into its own party platform. A third-party candidate will sometimes strike a chord with a section of voters in a particular election, bringing an issue to national prominence and amount a significant proportion of the popular vote. Major parties often respond to this by adopting this issue in a subsequent election. After 1968, under President Nixon the Republican Party adopted a "Southern Strategy" to win the support of conservative Democrats opposed to the Civil Rights Movement and resulting legislation and to combat local third parties. This can be seen as a response to the popularity of segregationist candidate George Wallace who gained 13.5% of the popular vote in the 1968 election for the American Independent Party. In 1996, both the Democrats and the Republicans agreed to deficit reduction on the back of Ross Perot's popularity in the 1992 election. This severely undermined Perot's campaign in the 1996 election.[citation needed]

However, changing positions can be costly for a major party. For example, in the US 2000 Presidential election Magee predicts that Gore shifted his positions to the left to account for Nader, which lost him some valuable centrist voters to Bush.[54] In cases with an extreme minor candidate, not changing positions can help to reframe the more competitive candidate as moderate, helping to attract the most valuable swing voters from their top competitor while losing some voters on the extreme to the less competitive minor candidate.[55]

Current U.S. third parties

[edit]

Largest

[edit]| Party | No. registrations[56] | % registered voters[56] |

|---|---|---|

| Libertarian Party | 732,865 | 0.6% |

| Green Party | 234,120 | 0.19% |

| Constitution Party | 128,914 | 0.11% |

| Working Families Party | 58,070 | 0.05% |

| Reform Party | 4,415 | nil |

Smaller parties (listed by ideology)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

This section includes only parties that have actually run candidates under their name in recent years.

Right-wing

[edit]This section includes any party that advocates positions associated with American conservatism, including both Old Right and New Right ideologies.

State-only right-wing parties

[edit]- American Independent Party (California)

- Conservative Party of New York State

- Constitution Party of Oregon

Centrist

[edit]This section includes any party that is independent, populist, or any other that either rejects left–right politics or does not have a party platform.

- Alliance Party

- American Solidarity Party

- Citizens Party

- Forward Party/Forward

- No Labels

- Reform Party of the United States of America

- United States Pirate Party

- Unity Party of America

State-only centrist parties

[edit]- Moderate Party of New Jersey

- Moderate Party of Rhode Island

- Independent Party of Delaware

- Independent Party of Oregon

- Keystone Party of Pennsylvania

- United Utah Party

- Colorado Center Party

Left-wing

[edit]This section includes any party that has a left-liberal, progressive, social democratic, democratic socialist, or Marxist platform.

- Communist Party USA

- Freedom Socialist Party

- People's Party

- Party for Socialism and Liberation

- Peace and Freedom Party

- Socialist Action

- Social Democrats, USA

- Socialist Equality Party

- Socialist Alternative

- Socialist Party USA

- Socialist Workers Party

- Working Class Party

- Workers World Party

- Working Families Party

State-only left-wing parties

[edit]- Charter Party (Cincinnati, Ohio, only)

- Green Mountain Peace and Justice Party (Vermont)

- Green Party of Alaska

- Green Party of Rhode Island

- Kentucky Party

- Labor Party (South Carolina Workers Party)

- Liberal Party of New York

- Oregon Progressive Party

- Progressive Dane (Dane county, Wisconsin)

- United Independent Party (Massachusetts)

- Vermont Progressive Party

- Washington Progressive Party

Ethnic nationalism

[edit]This section includes parties that primarily advocate for granting special privileges or consideration to members of a certain race, ethnic group, religion etc.

- American Freedom Party

- Black Riders Liberation Party

- National Socialist Movement

- New Afrikan Black Panther Party

Also included in this category are various parties found in and confined to Native American reservations, almost all of which are solely devoted to the furthering of the tribes to which the reservations were assigned. An example of a particularly powerful tribal nationalist party is the Seneca Party that operates on the Seneca Nation of New York's reservations.[57]

Secessionist parties

[edit]This section includes parties that primarily advocate for Independence from the United States. (Specific party platforms may range from left wing to right wing).

Single-issue/protest-oriented

[edit]This section includes parties that primarily advocate single-issue politics (though they may have a more detailed platform) or may seek to attract protest votes rather than to mount serious political campaigns or advocacy.

- Grassroots–Legalize Cannabis Party

- Legal Marijuana Now Party

- Prohibition Party

- United States Marijuana Party[citation needed]

State-only parties

[edit]- Approval Voting Party (Colorado)

- Natural Law Party (Michigan)

- New York State Right to Life Party

- Rent Is Too Damn High Party (New York)

1992

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross Perot | Independent | 19,743,821 | 18.91% | Maine: 30.44%

|

| Andre Verne Marrou | Libertarian | 290,087 | 0.28% | New Hampshire: 0.66%

|

| Bo Gritz | Populist | 106,152 | 0.10% | Utah: 3.84%

|

| Other | 269,507 | 0.24% | — | |

| Total | 20,409,567 | 19.53% | — | |

1996

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross Perot | Reform | 8,085,294 | 8.40% | Maine: 14.19%

|

| Ralph Nader | Green | 684,871 | 0.71% | Oregon: 3.59%

|

| Harry Browne | Libertarian | 485,759 | 0.50% | Arizona: 1.02%

|

| Other | 419,986 | 0.43% | — | |

| Total | 9,675,910 | 10.04% | — | |

2000

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Green | 2,882,955 | 2.74% | Alaska: 10.07%

|

| Pat Buchanan | Reform | 448,895 | 0.43% | North Dakota: 2.53%

|

| Harry Browne | Libertarian | 384,431 | 0.36% | Georgia: 1.40%

|

| Other | 232,920 | 0.22% | — | |

| Total | 3,949,201 | 3.75% | — | |

2004

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Independent | 465,650 | 0.38% | Alaska: 1.62%

|

| Michael Badnarik | Libertarian | 397,265 | 0.32% | Indiana: 0.73%

|

| Michael Peroutka | Constitution | 143,630 | 0.15% | Utah: 0.74%

|

| Other | 215,031 | 0.18% | — | |

| Total | 1,221,576 | 1.00% | — | |

2008

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Independent | 739,034 | 0.56% | Maine: 1.45%

|

| Bob Barr | Libertarian | 523,715 | 0.40% | Indiana: 1.06%

|

| Chuck Baldwin | Constitution | 199,750 | 0.12% | Utah: 1.26%

|

| Other | 404,482 | 0.31% | — | |

| Total | 1,866,981 | 1.39% | — | |

2012

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Libertarian | 1,275,971 | 0.99% | New Mexico: 3.60%

|

| Jill Stein | Green | 469,627 | 0.36% | |

| Virgil Goode | Constitution | 122,389 | 0.11% | Wyoming: 0.58%

|

| Other | 368,124 | 0.28% | — | |

| Total | 2,236,111 | 1.74% | — | |

2016

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Libertarian | 4,489,341 | 3.28% | New Mexico: 9.34%

|

| Jill Stein | Green | 1,457,218 | 1.07% | Hawaii: 2.97%

|

| Evan McMullin | Independent | 731,991 | 0.54% | Utah: 21.54%

|

| Other | 1,149,700 | 0.84% | — | |

| Total | 7,828,250 | 5.73% | — | |

2020

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jo Jorgensen | Libertarian | 1,865,535 | 1.18% | South Dakota: 2.63%

|

| Howie Hawkins | Green | 407,068 | 0.26% | Maine: 1.00%

|

| Rocky De La Fuente | Alliance | 88,241 | 0.06% | California: 0.34%

|

| Other | 561,311 | 0.41% | — | |

| Total | 2,922,155 | 1.85% | — | |

2024

[edit]In 2023 and 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. initially polled higher than any third-party presidential candidate since Ross Perot[58] in the 1992 and 1996 elections.[59][60][61] As Democrat Joe Biden withdrew from the race and the election grew closer, his poll numbers and notoriety would drop drastically.[62]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jill Stein | Green | 699,135 | 0.47% | TBD

|

| Robert F. Kennedy Jr. | Independent | 681,450 | 0.46% | TBD

|

| Chase Oliver | Libertarian | 604,283 | 0.41% | TBD

|

| Randall Terry | Constitution Party | 40,882 | 0.03% | TBD

|

| Other | TBD | TBD | — | |

| Total | TBD | TBD | — | |

Map

[edit]State wins

[edit]-

1892 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by James B. Weaver of the Populist Party.

-

1912 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by Theodore Roosevelt of the Progressive Party.

-

1924 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by Robert M. La Follette of the Progressive Party.

-

1948 United States presidential election; orange denotes electoral votes won by Strom Thurmond of the Dixiecrat.

-

1968 United States presidential election; Brown denotes electoral votes won by George Wallace of the American Independent Party.

Vote percentages

[edit]-

2000 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Green candidate Ralph Nader

-

2016 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson

-

2016 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Green candidate Jill Stein

Notes

[edit]- ^ STV was used in 2010 to elect 25 members at large in the 2010 Icelandic Constitutional Assembly election.

References

[edit]- ^ a b O'Neill, Aaron (June 21, 2022). "U.S. presidential elections: third-party performance 1892-2020". Statista. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger, ed. History of US political parties (5 vol. Chelsea House Pub, 2002).

- ^ Masket, Seth (Fall 2023). "Giving Minor Parties a Chance". Democracy. 70.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (November 25, 2021). "Why are there only two parties in American politics?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Riker, William H. (December 1982). "The Two-party System and Duverger's Law: An Essay on the History of Political Science". American Political Science Review. 76 (4): 753–766. doi:10.1017/s0003055400189580. JSTOR 1962968. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Nichols, John (2011). The "S" Word: A Short History of an American Tradition. Verso. p. 104. ISBN 9781844676798.

- ^ Kettle, Martin (February 12, 2000). "Ventura quits Perot's Reform party". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Senator Lisa Murkowski wins Alaska write-in campaign". Reuters. November 18, 2010. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Zeller, Shawn. "Crashing the Lieberman Party". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Justin Amash Becomes the First Libertarian Member of Congress". Reason.com. April 29, 2020. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Mitchell, Maurice; Cantor, Dan (March 22, 2019). "In Defense of Fusion Voting". The Nation.

- ^ Abadi, Mark (November 8, 2016). "This is why some candidates are listed more than once on your ballot". Business Insider.

- ^ "What is Fusion" (PDF). Oregon Working Families Party. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2012.

- ^ "Brief for appellant: Twin Cities Area New Party vs Secretary of State of Minnesota". Public Citizen Foundation.

- ^ "The Realistic Promise of Multiparty Democracy in the United States". New America. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Fusion Voting and Its Impact on the Upcoming Election". New York Law Journal. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Does Fusion Voting Offer Americans a Way Out of the Partisan Morass?". The New York Times.

- ^ "WHERE IS RCV USED?". RCV Resources. Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Where is Ranked Choice Voting Used?". FairVote. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Perspective | How ranked-choice voting saved the Virginia GOP from itself". Washington Post. November 5, 2021. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "Ranked Choice Voting in Utah". Utah Ranked Choice Voting. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "2020 State Convention". The Indiana Republican Party. May 20, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ Mill, John Stuart (1861). "Chapter VII, Of True and False Democracy; Representation of All, and Representation of the Majority only". Considerations on Representative Government. London: Parker, Son, & Bourn.

- ^ ACE Project: The Electoral Knowledge Network. "Electoral Systems Comparative Data, Table by Question". Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Amy, Douglas J. "How Proportional Representation Elections Work". FairVote. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Gallagher, Michael. "Ireland: The Archetypal Single Transferable Vote System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Hirczy de Miño, Wolfgang; Lane, John (1999). "Malta: STV in a two-party system" (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "Rajya Sabha Introduction".

- ^ Algeria's largest district has 37 deputies (p. 15): https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/election_reports/algeria-may2012-final-rpt.pdf

- ^ Laakso, Markku (1980). "Electoral Justice as a Criterion for Different Systems of Proportional Representation". Scandinavian Political Studies. 3 (3). Wiley: 249–264. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1980.tb00248.x. ISSN 0080-6757.

- ^ Naylor, Brian (October 7, 2020). "How Maine's Ranked-Choice Voting System Works". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Sifry, Micah L. (February 2, 2018). "Why America Is Stuck With Only Two Parties". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Selk, Avi (November 25, 2021). "Analysis | Green Party candidate says he might be part alien, doesn't care if he's a spoiler in Ohio election". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Means, Marianne (February 4, 2001). "Opinion: Goodbye, Ralph". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on May 26, 2002.

- ^ Green, Donald J. (2010). Third-party matters: politics, presidents, and third parties in American history. Santa Barbara, Calif: Praeger. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-313-36591-1.

- ^ Devine, Christopher J.; Kopko, Kyle C. (September 1, 2021). "Did Gary Johnson and Jill Stein Cost Hillary Clinton the Presidency? A Counterfactual Analysis of Minor Party Voting in the 2016 US Presidential Election". The Forum. 19 (2): 173–201. doi:10.1515/for-2021-0011. ISSN 1540-8884. S2CID 237457376.

- ^ Herron, Michael C.; Lewis, Jeffrey B. (April 24, 2006). "Did Ralph Nader spoil Al Gore's Presidential bid? A ballot-level study of Green and Reform Party voters in the 2000 Presidential election". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2 (3). Now Publishing Inc.: 205–226. doi:10.1561/100.00005039. Pdf.

- ^ Burden, Barry C. (September 2005). "Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election". American Politics Research. 33 (5): 672–699. doi:10.1177/1532673x04272431. ISSN 1532-673X. S2CID 43919948.

- ^ Roberts, Joel (July 27, 2004). "Nader to crash Dems' party?". CBS News.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie et al (September 22, 2020) "How Republicans Are Trying to Use the Green Party to Their Advantage." New York Times. (Retrieved September 24, 2020.)

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Hakim, Danny; Corasaniti, Nick (September 22, 2020). "How Republicans Are Trying to Use the Green Party to Their Advantage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Schreckinger, Ben (June 20, 2017). "Jill Stein Isn't Sorry". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "Russians launched pro-Jill Stein social media blitz to help Trump, reports say". NBC News. December 22, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Amato, Theresa (December 4, 2009). "The two party ballot suppresses third party change". The Record. Harvard Law. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

Today, as in 1958, ballot access for minor parties and Independents remains convoluted and discriminatory. Though certain state ballot access statutes are better, and a few Supreme Court decisions (Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968), Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1983)) have been generally favorable, on the whole, the process—and the cumulative burden it places on these federal candidates—may be best described as antagonistic. The jurisprudence of the Court remains hostile to minor party and Independent candidates, and this antipathy can be seen in at least a half dozen cases decided since Nader's article, including Jenness v. Fortson, 403 U.S. 431 (1971), American Party of Tex. v. White, 415 U.S. 767 (1974), Munro v. Socialist Workers Party, 479 U.S. 189 (1986), Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428 (1992), and Arkansas Ed. Television Comm'n v. Forbes, 523 U.S. 666 (1998). Justice Rehnquist, for example, writing for a 6–3 divided Court in Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party, 520 U.S. 351 (1997), spells out the Court's bias for the "two-party system," even though the word "party" is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. He wrote that "The Constitution permits the Minnesota Legislature to decide that political stability is best served through a healthy two-party system. And while an interest in securing the perceived benefits of a stable two-party system will not justify unreasonably exclusionary restrictions, States need not remove all the many hurdles third parties face in the American political arena today." 520 U.S. 351, 366–67.

- ^ "What Happened in 1992?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Caldwell, Nicole (October 7, 2020). "A Look Back at the History of Presidential Debates". Newsweek. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "What Happened in 1996?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "The Commission on Presidential Debates: An Overview". Commission on Presidential Debates. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites and Dates for 2024 General Election Debates and 2024 Nonpartisan Candidate Selection Criteria". Commission on Presidential Debates. November 30, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites and Dates for 2020 General Election Debates and 2020 Nonpartisan Candidate Selection Criteria". Commission on Presidential Debates. October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates Announces 2016 Nonpartisan Candidate Selection Criteria; Forms Working Group on Format". Commission on Presidential Debates. October 29, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites, Dates, and Candidate Selection Criteria for 2012 General Election". Commission on Presidential Debates. October 31, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites, Dates, Formats and Candidate Selection Criteria for 2008 General Election". Commission on Presidential Debates. November 19, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Magee, Christopher S. P. (2003). "Third-Party Candidates and the 2000 Presidential Election". Social Science Quarterly. 84 (3): 574–595. doi:10.1111/1540-6237.8403006. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 42955889.

- ^ Wang, Austin Horng-En; Chen, Fang-Yu (2019). "Extreme Candidates as the Beneficent Spoiler? Range Effect in the Plurality Voting System". Political Research Quarterly. 72 (2): 278–292. doi:10.1177/1065912918781049. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45276909. S2CID 54056894.

- ^ a b Winger, Richard (December 27, 2022). "December 2022 Ballot Access News Print Edition". Ballot Access News. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Herbeck, Dan (November 15, 2011). Resentments abound in Seneca power struggle Archived November 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Buffalo News. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Nuzzi, Olivia (November 22, 2023). "The Mind-Bending Politics of RFK Jr". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on March 6, 2024. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

The general election is now projected to be a three-way race between Biden, Trump, and their mutual, Kennedy, with a cluster of less popular third-party candidates filling out the constellation.

- ^ Benson, Samuel (November 2, 2023). "RFK Jr.'s big gamble". Deseret News. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

Early polls show Kennedy polling in the teens or low 20s

- ^ Enten, Harry (November 11, 2023). "How RFK Jr. could change the outcome of the 2024 election". CNN. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Collins, Eliza (March 26, 2024). "RFK Jr. to Name Nicole Shanahan as Running Mate for Presidential Bid". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Koretski, Katherine (August 8, 2024). "RFK Jr.'s incredible disappearing campaign". NBC News. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Tamas, Bernard. 2018. The Demise and Rebirth of American Third Parties: Poised for Political Revival? Routledge.

- Epstein, David A. (2012). Left, Right, Out: The History of Third Parties in America. Arts and Letters Imperium Publications. ISBN 978-0-578-10654-0

- Gillespie, J. David. Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics (University of South Carolina Press, 2012)

- Ness, Immanuel and James Ciment, eds. Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America (4 vol. 2006) (2000 edition)

External links

[edit]- "Third-party voters face a tough choice in a tight election" (September 22, 2024) by NPR