Duodenum

| Duodenum | |

|---|---|

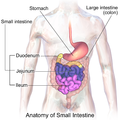

Image of the gastrointestinal tract, with the duodenum highlighted. | |

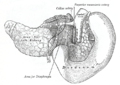

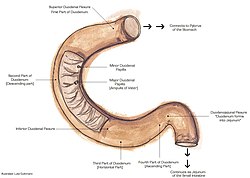

Diagram of the human duodenum with major parts labelled | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˌdjuːəˈdiːnəm/, US also /djuˈɒdɪnəm/[2] |

| Precursor | Foregut (1st and 2nd parts), midgut (3rd and 4th part) |

| Part of | Small intestine |

| System | Digestive system |

| Artery | Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, superior pancreaticoduodenal artery |

| Vein | Pancreaticoduodenal veins |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | duodenum |

| MeSH | D004386 |

| TA98 | A05.6.02.001 |

| TA2 | 2944 |

| FMA | 7206 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine[3] in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption. The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest part of the small intestine.

In human beings, the duodenum is a hollow jointed tube about 25–38 centimetres (10–15 inches) long connecting the stomach to the middle part of the small intestine.[4][5] It begins with the duodenal bulb and ends at the suspensory muscle of duodenum.[6] The duodenum can be divided into four parts: the first (superior), the second (descending), the third (transverse) and the fourth (ascending) parts.[5]

Overview

[edit]The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine may be used instead of duodenum.[7] In mammals the duodenum may be the principal site for iron absorption.[8]

In humans, the duodenum is a C-shaped hollow jointed tube, 25–38 centimetres (10–15 inches) in length, lying adjacent to the stomach (and connecting it to the small intestine). It is divided anatomically into four sections. The first part lies within the peritoneum but its other parts are retroperitoneal.[9]: 273

Parts

[edit]The first part, or superior part, of the duodenum is a continuation from the pylorus to the transpyloric plane. It is superior (above) to the rest of the segments, at the vertebral level of L1. The duodenal bulb, about 2 cm (3⁄4 in) long, is the first part of the duodenum and is slightly dilated. The duodenal bulb is a remnant of the mesoduodenum, a mesentery that suspends the organ from the posterior abdominal wall in fetal life.[10] The first part of the duodenum is mobile, and connected to the liver by the hepatoduodenal ligament of the lesser omentum. The first part of the duodenum ends at the corner, the superior duodenal flexure.[9]: 273

Relations:[citation needed]

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Superior

- Inferior

The second part, or descending part, of the duodenum begins at the superior duodenal flexure. It goes inferior to the lower border of vertebral body L3, before making a sharp turn medially into the inferior duodenal flexure, the end of the descending part.[9]: 274

The pancreatic duct and common bile duct enter the descending duodenum, through the major duodenal papilla. The second part of the duodenum also contains the minor duodenal papilla, the entrance for the accessory pancreatic duct. The junction between the embryological foregut and midgut lies just below the major duodenal papilla.[9]: 274

The third part, or horizontal part or inferior part of the duodenum is 10~12 cm in length. It begins at the inferior duodenal flexure and passes transversely to the left, passing in front of the inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta and the vertebral column. The superior mesenteric artery and vein are anterior to the third part of the duodenum.[9]: 274 This part may be compressed between the aorta and SMA causing superior mesenteric artery syndrome.

The fourth part, or ascending part, of the duodenum passes upward, joining with the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure. The fourth part of the duodenum is at the vertebral level L3, and may pass directly on top, or slightly to the left, of the aorta.[9]: 274

Blood supply

[edit]The duodenum receives arterial blood from two different sources. The transition between these sources is important as it demarcates the foregut from the midgut. Proximal to the 2nd part of the duodenum (approximately at the major duodenal papilla – where the bile duct enters) the arterial supply is from the gastroduodenal artery and its branch the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. Distal to this point (the midgut) the arterial supply is from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and its branch the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery supplies the 3rd and 4th sections. The superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (from the gastroduodenal artery and SMA respectively) form an anastomotic loop between the celiac trunk and the SMA; so there is potential for collateral circulation here.

The venous drainage of the duodenum follows the arteries. Ultimately these veins drain into the portal system, either directly or indirectly through the splenic or superior mesenteric vein and then to the portal vein.

Lymphatic drainage

[edit]The lymphatic vessels follow the arteries in a retrograde fashion. The anterior lymphatic vessels drain into the pancreatoduodenal lymph nodes located along the superior and inferior pancreatoduodenal arteries and then into the pyloric lymph nodes (along the gastroduodenal artery). The posterior lymphatic vessels pass posterior to the head of the pancreas and drain into the superior mesenteric lymph nodes. Efferent lymphatic vessels from the duodenal lymph nodes ultimately pass into the celiac lymph nodes.

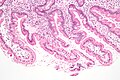

Histology

[edit]Under microscopy, the duodenum has a villous mucosa. This is distinct from the mucosa of the pylorus, which directly joins the duodenum. Like other structures of the gastrointestinal tract, the duodenum has a mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and adventitia. Glands line the duodenum, known as Brunner's glands, which secrete mucus and bicarbonate in order to neutralise stomach acids. These are distinct glands not found in the ileum or jejunum, the other parts of the small intestine.[11]: 274–275

-

Dog duodenum 100X

-

Duodenum with amyloid deposition in lamina propria

-

Section of duodenum of cat. X 60

-

Duodenum with brush border (microvillus)

Variation

[edit]The duodenum's close anatomical association with the pancreas creates differences in function based on the position and orientation of the organs. The congenital abnormality, annular pancreas, causes a portion of the pancreas to encircle the duodenum. In an extramural annular pancreas, the pancreatic duct encircles the duodenum which results in gastrointestinal obstruction. An intramural annular pancreas is characterized by pancreatic tissue that is fused with the duodenal wall, causing duodenal ulceration.[12]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2013) |

Gene and protein expression

[edit]About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal duodenum.[13][14] Some 300 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the duodenum with very few genes expressed only in the duodenum. The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the duodenal mucosa, and many of these are also expressed in the small intestine, such as alanine aminopeptidase, a digestive enzyme, angiotensin-converting enzyme, involved in controlling blood pressure, and RBP2, a protein involved in the uptake of vitamin A.[15]

Function

[edit]The duodenum is largely responsible for the breakdown of food in the small intestine, using enzymes. The duodenum also regulates the rate of emptying of the stomach via hormonal pathways. Secretin and cholecystokinin are released from cells in the duodenal epithelium in response to acidic and fatty stimuli present there when the pylorus opens and emits gastric chyme into the duodenum for further digestion. These cause the liver and gallbladder to release bile, and the pancreas to release bicarbonate and digestive enzymes such as trypsin, lipase and amylase into the duodenum as they are needed.[16]

The duodenum is a critical contributor to the regulation of food intake[17] and glycemic control.[18] As the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum is the initial site of nutrient absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. The duodenum senses nutrient intake and composition, and signals to the liver, pancreas, adipose tissue and brain[19] through the direct and indirect[20] release of several key hormones and signaling molecules, including the incretin peptides Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1),[20] as well as Cholecystokinin (CCK) and Secretin. The duodenum also signals to the brain directly via vagal afferents enabling neural control over food intake and glycemia.[21] Intestinal secretion of GIP and GLP-1 stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells, known as the incretin effect.[22] Incretin peptides, principally GLP-1 and GIP, regulate islet hormone secretion, glucose concentrations, lipid metabolism, gut motility, appetite and body weight, and immune function.[23]

The villi of the duodenum have a leafy-looking appearance, which is a histologically identifiable structure. Brunner's glands, which secrete mucus, are only found in the duodenum. The duodenum wall consists of a very thin layer of cells that form the muscularis mucosae.

Clinical significance

[edit]Ulceration

[edit]Ulcers of the duodenum commonly occur because of infection by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori. These bacteria, through a number of mechanisms, erode the protective mucosa of the duodenum, predisposing it to damage from gastric acids. The first part of the duodenum is the most common location of ulcers since it is where the acidic chyme meets the duodenal mucosa before mixing with the alkaline secretions of the duodenum.[24] Duodenal ulcers may cause recurrent abdominal pain and dyspepsia, and are often investigated using a urea breath test to test for the bacteria, and endoscopy to confirm ulceration and take a biopsy. If managed, these are often managed through antibiotics that aim to eradicate the bacteria, and proton-pump inhibitors and antacids to reduce the gastric acidity.[25]

Celiac disease

[edit]The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines specify that a duodenal biopsy is required for the diagnosis of adult celiac disease. The biopsy is ideally performed at a moment when the patient is on a gluten-containing diet.[26]

Cancer

[edit]Duodenal cancer is a cancer in the first section of the small intestine. Cancer of the duodenum is relatively rare compared to stomach cancer and colorectal cancer; malignant tumors in the duodenum constitute only around 0.3% of all the gastrointestinal tract tumors but around half of cancerous tissues that develop in the small intestine.[27] Its histology is often observed to be adenocarcinoma, meaning that the cancerous tissue arises from glandular cells in the epithelial tissue lining the duodenum.[28]

Obesity and Diabetes

[edit]A western diet induces duodenal mucosal hyperplasia and dysfunction that underlie insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and obesity.[29][30] Diet-induced duodenal mucosal hyperplasia consists of increased mucosal mass,[31] increased villus length,[29][32][33][34] decreased crypt density,[29] proliferation of enteroendocrine cells,[35] increased enterocyte mass,[36] and an accumulation of lipid droplets in the mucosa.[37][38] Diet induced duodenal dysfunction includes increased duodenal nutrient absorption,[32] altered duodenal hormone secretion,[29] and altered intestinal vagal afferent neuronal function.[39]

Inflammation

[edit]Inflammation of the duodenum is referred to as duodenitis. There are multiple known causes.[40] Celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease are two of the known causes.[41]

Etymology

[edit]The name duodenum is Medieval Latin, short for intestīnum duodēnum digitōrum, meaning intestine of twelve finger-widths (in length), genitive pl. of duodēnī, twelve each, from Latin duodeni "twelve each" (from duodecim "twelve"). Coined by Gerard of Cremona (d. 1187) in his Latin translation of "Canon Avicennae," "اثنا عشر" itself a loan-translation of Greek dodekadaktylon, literally "twelve fingers long." The intestine part was so called by the Greek physician Herophilus (c. 335–280 BCE) for its length, about equal to the breadth of 12 fingers.[42]

Many languages retain a similar etymology for this word. For example, German Zwölffingerdarm, Dutch Twaalfvingerige darm and Turkish Oniki parmak bağırsağı.

Additional images

[edit]-

Sections of the small intestine

-

The celiac artery and its branches; the stomach has been raised and the peritoneum removed

-

Superior and inferior duodenal fossæ

-

Duodenojejunal fossa

-

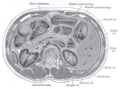

The pancreas and duodenum from behind

-

Transverse section through the middle of the first lumbar vertebra, showing the relations of the pancreas

-

The pancreatic duct

-

Region of pancreas

-

Duodenum

-

Duodenum

-

Duodenum

See also

[edit]- Pancreas

- Choledochoduodenostomy - a surgical procedure to create a connection between the common bile duct (CBD) and an alternative portion of the duodenum.

References

[edit]- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

The first part of the small intestine. It connects to the stomach. The duodenum helps to further digest food coming from the stomach. It absorbs nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins) and water from food so they can be used by the body.

- ^ "Duodenum: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

It is located between the stomach and the middle part of the small intestine. After foods mix with stomach acid, they move into the duodenum, where they mix with bile from the gallbladder and digestive juices from the pancreas.

- ^ a b Nolan, D. J. (2002). "Radiology of the Duodenum". Radiological Imaging of the Small Intestine. Medical Radiology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 247–259. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56231-0_6. ISBN 978-3-642-62993-8. ISSN 0942-5373.

duodenum is a C-shaped hollow organ forming an incomplete circle around the head of the pancreas. ...it is normally examined as part of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- ^ van Gijn J; Gijselhart JP (2011). "Treitz and his ligament". Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 155 (8): A2879. PMID 21557825.

- ^ Guillaume, Jean; Praxis Publishing; Sadasivam Kaushik; Pierre Bergot; Robert Metailler (2001). Nutrition and Feeding of Fish and Crustaceans. Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-85233-241-9. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ Latunde-Dada GO; Van der Westhuizen J; Vulpe CD; et al. (2002). "Molecular and functional roles of duodenal cytochrome B (Dcytb) in iron metabolism". Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 29 (3): 356–60. doi:10.1006/bcmd.2002.0574. PMID 12547225.

- ^ a b c d e f Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ Singh, Inderbir; GP Pal (2012). "13". Human Embryology (9 ed.). Delhi: Macmillan Publishers India. p. 163. ISBN 978-93-5059-122-2.

- ^ Deakin, Barbara Young; et al. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas (5th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ^ Borghei, Peyman; Sokhandon, Farnoosh; Shirkhoda, Ali; Morgan, Desiree E. (January 2013). "Anomalies, Anatomic Variants, and Sources of Diagnostic Pitfalls in Pancreatic Imaging". Radiology. 266 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1148/radiol.12112469. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 23264525.

- ^ "The human proteome in duodenum - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Gremel, Gabriela; Wanders, Alkwin; Cedernaes, Jonathan; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn; Edlund, Karolina; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Uhlén, Mathias; Pontén, Fredrik (2015-01-01). "The human gastrointestinal tract-specific transcriptome and proteome as defined by RNA sequencing and antibody-based profiling". Journal of Gastroenterology. 50 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1007/s00535-014-0958-7. ISSN 0944-1174. PMID 24789573. S2CID 21302849.

- ^ Chandra, Rashmi; Liddle, Rodger A. (September 2014). "Recent advances in the regulation of pancreatic secretion". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 30 (5): 490–494. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000099. ISSN 0267-1379. PMC 4229368. PMID 25003603.

- ^ Woodward, Orla R. M.; Gribble, Fiona M.; Reimann, Frank; Lewis, Jo E. (2022). "Gut peptide regulation of food intake – evidence for the modulation of hedonic feeding". The Journal of Physiology. 600 (5): 1053–1078. doi:10.1113/JP280581. ISSN 1469-7793. PMID 34152020.

- ^ Drucker, Daniel J. (2006-03-01). "The biology of incretin hormones". Cell Metabolism. 3 (3): 153–165. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. ISSN 1550-4131. PMID 16517403.

- ^ Bany Bakar, Rula; Reimann, Frank; Gribble, Fiona M. (December 2023). "The intestine as an endocrine organ and the role of gut hormones in metabolic regulation". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 20 (12): 784–796. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00830-y. ISSN 1759-5053. PMID 37626258.

- ^ a b Hansen, Lene; Holst, Jens J (2002-12-31). "The effects of duodenal peptides on glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from the ileum: A duodeno–ileal loop?". Regulatory Peptides. 110 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1016/S0167-0115(02)00157-X. ISSN 0167-0115. PMID 12468108.

- ^ Thorens, Bernard; Larsen, Philip Just (July 2004). "Gut-derived signaling molecules and vagal afferents in the control of glucose and energy homeostasis". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 7 (4): 471–478. doi:10.1097/01.mco.0000134368.91900.84. ISSN 1363-1950. PMID 15192452.

- ^ Nauck, Michael A.; Meier, Juris J. (February 2018). "Incretin hormones: Their role in health and disease". Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 20 (S1): 5–21. doi:10.1111/dom.13129. ISSN 1462-8902. PMID 29364588.

- ^ Campbell, Jonathan E.; Drucker, Daniel J. (2013-06-04). "Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action". Cell Metabolism. 17 (6): 819–837. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.008. ISSN 1932-7420. PMID 23684623.

- ^ Smith, Margaret E. The Digestive System.

- ^ Colledge, Nicki R.; Walker, Brian R.; Ralston, Stuart H., eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 871–874. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ^ Ludvigsson, J. F.; Bai, J. C.; Biagi, F.; Card, T. R.; Ciacci, C.; Ciclitira, P. J.; Green, P. H. R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Holdoway, A.; van Heel, D. A.; Kaukinen, K.; Leffler, D. A.; Leonard, J. N.; Lundin, K. E. A.; McGough, N.; Davidson, M.; Murray, J. A.; Swift, G. L.; Walker, M. M.; Zingone, F.; Sanders, D. S. (2014). "Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology". Gut. 63 (8): 1210–1228. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. ISSN 0017-5749. PMC 4112432. PMID 24917550.

- ^ Fagniez, Pierre-Louis; Rotman, Nelly (2001). Malignant tumors of the duodenum. Zuckschwerdt.

- ^ "Definition of adenocarcinoma - NCI Dictionnary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Aliluev, Alexandra; Tritschler, Sophie; Sterr, Michael; Oppenländer, Lena; Hinterdobler, Julia; Greisle, Tobias; Irmler, Martin; Beckers, Johannes; Sun, Na; Walch, Axel; Stemmer, Kerstin; Kindt, Alida; Krumsiek, Jan; Tschöp, Matthias H.; Luecken, Malte D. (2021-09-22). "Diet-induced alteration of intestinal stem cell function underlies obesity and prediabetes in mice". Nature Metabolism. 3 (9): 1202–1216. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00458-9. ISSN 2522-5812. PMC 8458097. PMID 34552271.

- ^ Clara, Rosmarie; Schumacher, Manuel; Ramachandran, Deepti; Fedele, Shahana; Krieger, Jean-Philippe; Langhans, Wolfgang; Mansouri, Abdelhak (January 2017). "Metabolic Adaptation of the Small Intestine to Short- and Medium-Term High-Fat Diet Exposure: INTESTINAL METABOLIC ADAPTATION TO HFD". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 232 (1): 167–175. doi:10.1002/jcp.25402. PMID 27061934.

- ^ Hvid, Henning; Jensen, Stina Rikke; Witgen, Brent M.; Fledelius, Christian; Damgaard, Jesper; Pyke, Charles; Rasmussen, Thomas Bovbjerg (2016). "Diabetic Phenotype in the Small Intestine of Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats". Digestion. 94 (4): 199–214. doi:10.1159/000453107. ISSN 0012-2823. PMID 27931035.

- ^ a b Taylor, Samuel R.; Ramsamooj, Shakti; Liang, Roger J.; Katti, Alyna; Pozovskiy, Rita; Vasan, Neil; Hwang, Seo-Kyoung; Nahiyaan, Navid; Francoeur, Nancy J.; Schatoff, Emma M.; Johnson, Jared L.; Shah, Manish A.; Dannenberg, Andrew J.; Sebra, Robert P.; Dow, Lukas E. (2021-09-09). "Dietary fructose improves intestinal cell survival and nutrient absorption". Nature. 597 (7875): 263–267. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03827-2. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 8686685. PMID 34408323.

- ^ Dailey, Megan J. (September 2014). "Nutrient-induced intestinal adaption and its effect in obesity". Physiology & Behavior. 136: 74–78. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.026. PMC 4182169. PMID 24704111.

- ^ Sagher, F. A.; Dodge, J. A.; Johnston, C. F.; Shaw, C.; Buchanan, K. D.; Carr, K. E. (1991). "Rat small intestinal morphology and tissue regulatory peptides: effects of high dietary fat". British Journal of Nutrition. 65 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1079/BJN19910062. ISSN 0007-1145. PMID 1705145.

- ^ Gniuli, D.; Calcagno, A.; Dalla Libera, L.; Calvani, R.; Leccesi, L.; Caristo, M. E.; Vettor, R.; Castagneto, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; Mingrone, G. (October 2010). "High-fat feeding stimulates endocrine, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)-expressing cell hyperplasia in the duodenum of Wistar rats". Diabetologia. 53 (10): 2233–2240. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1830-9. ISSN 0012-186X. PMID 20585935.

- ^ Verdam, Froukje J.; Greve, Jan Willem M.; Roosta, Sedigheh; van Eijk, Hans; Bouvy, Nicole; Buurman, Wim A.; Rensen, Sander S. (2011-02-01). "Small Intestinal Alterations in Severely Obese Hyperglycemic Subjects". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 96 (2): E379 – E383. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1333. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 21084402.

- ^ Sferra, Roberta; Pompili, Simona; Cappariello, Alfredo; Gaudio, Eugenio; Latella, Giovanni; Vetuschi, Antonella (2021-07-06). "Prolonged Chronic Consumption of a High Fat with Sucrose Diet Alters the Morphology of the Small Intestine". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (14): 7280. doi:10.3390/ijms22147280. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8303301. PMID 34298894.

- ^ D’Aquila, Theresa; Zembroski, Alyssa S.; Buhman, Kimberly K. (2019-03-05). "Diet Induced Obesity Alters Intestinal Cytoplasmic Lipid Droplet Morphology and Proteome in the Postprandial Response to Dietary Fat". Frontiers in Physiology. 10: 180. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00180. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 6413465. PMID 30890954.

- ^ de Lartigue, Guillaume; Barbier de la Serre, Claire; Espero, Elvis; Lee, Jennifer; Raybould, Helen E. (2012-03-07). Gaetani, Silvana (ed.). "Leptin Resistance in Vagal Afferent Neurons Inhibits Cholecystokinin Signaling and Satiation in Diet Induced Obese Rats". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e32967. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032967. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3296757. PMID 22412960.

- ^ Serra S, Jani PA (2006). "An approach to duodenal biopsies". J. Clin. Pathol. 59 (11): 1133–50. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.031260. PMC 1860495. PMID 16679353.

- ^ Alper, Arik; Hardee, Steven; Rojas-velasquez, Danilo; Escalera, Sandra; Morotti, Raffaella A; Pashankar, Dinesh S. (February 2016). "Prevalence, clinical, endoscopic and pathological features of duodenitis in children". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 62 (2): 314–316. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000942. ISSN 0277-2116. PMC 4724230. PMID 26252915.

- ^ "duodenum - Origin and meaning of duodenum by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

External links

[edit]- Duodenum at the Human Protein Atlas

- Duodenum at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)