Instructional design

Instructional design (ID), also known as instructional systems design and originally known as instructional systems development (ISD), is the practice of systematically designing, developing and delivering instructional materials and experiences, both digital and physical, in a consistent and reliable fashion toward an efficient, effective, appealing, engaging and inspiring acquisition of knowledge.[1][2] The process consists broadly of determining the state and needs of the learner, defining the end goal of instruction, and creating some "intervention" to assist in the transition. The outcome of this instruction may be directly observable and scientifically measured or completely hidden and assumed.[3] There are many instructional design models, but many are based on the ADDIE model with the five phases: analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]As a field, instructional design is historically and traditionally rooted in cognitive and behavioral psychology, though recently constructivism has influenced thinking in the field.[4][5][6] This can be attributed to the way it emerged during a period when the behaviorist paradigm was dominating American psychology. There are also those who cite that, aside from behaviorist psychology, the origin of the concept could be traced back to systems engineering. While the impact of each of these fields is difficult to quantify, it is argued that the language and the "look and feel" of the early forms of instructional design and their progeny were derived from this engineering discipline.[7] Specifically, they were linked to the training development model used by the U.S. military, which were based on systems approach and was explained as "the idea of viewing a problem or situation in its entirety with all its ramifications, with all its interior interactions, with all its exterior connections and with full cognizance of its place in its context."[8]

The role of systems engineering in the early development of instructional design was demonstrated during World War II when a considerable amount of training materials for the military were developed based on the principles of instruction, learning, and human behavior. Tests for assessing a learner's abilities were used to screen candidates for the training programs. After the success of military training, psychologists began to view training as a system and developed various analysis, design, and evaluation procedures.[9] In 1946, Edgar Dale outlined a hierarchy of instructional methods, organized intuitively by their concreteness.[10][11] The framework first migrated to the industrial sector to train workers before it finally found its way to the education field.[12]

1950s

[edit]

B. F. Skinner's 1954 article "The Science of Learning and the Art of Teaching" suggested that effective instructional materials, called programmed instructional materials, should include small steps, frequent questions, and immediate feedback; and should allow self-pacing.[9] Robert F. Mager popularized the use of learning objectives with his 1962 article "Preparing Objectives for Programmed Instruction". The article describes how to write objectives including desired behavior, learning condition, and assessment.[9]

In 1956, a committee led by Benjamin Bloom published an influential taxonomy with three domains of learning: cognitive (what one knows or thinks), psychomotor (what one does, physically) and affective (what one feels, or what attitudes one has). These taxonomies still influence the design of instruction.[10][13]

1960s

[edit]Robert Glaser introduced "criterion-referenced measures" in 1962. In contrast to norm-referenced tests in which an individual's performance is compared to group performance, a criterion-referenced test is designed to test an individual's behavior in relation to an objective standard. It can be used to assess the learners' entry level behavior, and to what extent learners have developed mastery through an instructional program.[9]

In 1965, Robert Gagné described three domains of learning outcomes (cognitive, affective, psychomotor), five learning outcomes (Verbal Information, Intellectual Skills, Cognitive Strategy, Attitude, Motor Skills), and nine events of instruction in The Conditions of Learning, which remain foundations of instructional design practices.[9] Gagne's work in learning hierarchies and hierarchical analysis led to an important notion in instruction – to ensure that learners acquire prerequisite skills before attempting superordinate ones.[9]

In 1967, after analyzing the failure of training material, Michael Scriven suggested the need for formative assessment – e.g., to try out instructional materials with learners (and revise accordingly) before declaring them finalized.[9]

1970s

[edit]During the 1970s, the number of instructional design models greatly increased and prospered in different sectors in military, academia, and industry.[9] Many instructional design theorists began to adopt an information-processing-based approach to the design of instruction. David Merrill for instance developed Component Display Theory (CDT), which concentrates on the means of presenting instructional materials (presentation techniques).[14]

1980s

[edit]Although interest in instructional design continued to be strong in business and the military, there was little evolution of ID in schools or higher education.[9][15] However, educators and researchers began to consider how the personal computer could be used in a learning environment or a learning space.[9][10][16] PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operation) is one example of how computers began to be integrated into instruction.[17] Many of the first uses of computers in the classroom were for "drill and skill" exercises.[18] There was a growing interest in how cognitive psychology could be applied to instructional design.[10]

1990s

[edit]The influence of constructivist theory on instructional design became more prominent in the 1990s as a counterpoint to the more traditional cognitive learning theory.[15][19] Constructivists believe that learning experiences should be "authentic" and produce real-world learning environments that allow learners to construct their own knowledge.[15] This emphasis on the learner was a significant departure away from traditional forms of instructional design.[9][10][19]

Performance improvement was also seen as an important outcome of learning that needed to be considered during the design process.[9][16] The World Wide Web emerged as an online learning tool with hypertext and hypermedia being recognized as good tools for learning.[17] As technology advanced and constructivist theory gained popularity, technology's use in the classroom began to evolve from mostly drill and skill exercises to more interactive activities that required more complex thinking on the part of the learner.[18] Rapid prototyping was first seen during the 1990s. In this process, an instructional design project is prototyped quickly and then vetted through a series of try and revise cycles. This is a big departure from traditional methods of instructional design that took far longer to complete.[15]

The concept of learning design arrived in the literature of technology for education in the late 1990s and early 2000s[20] with the idea that "designers and instructors need to choose for themselves the best mixture of behaviourist and constructivist learning experiences for their online courses".[21] But the concept of learning design is probably as old as the concept of teaching. Learning design might be defined as "the description of the teaching-learning process that takes place in a unit of learning (e.g., a course, a lesson or any other designed learning event)".[22] As summarized by Britain,[23] learning design may be associated with:

- The concept of learning design

- The implementation of the concept made by learning design specifications like PALO, IMS Learning Design,[24] LDL, SLD 2.0, etc.

- The technical realisations around the implementation of the concept like TELOS, RELOAD LD-Author, etc.

2000 - 2010

[edit]Online learning became common.[9][25][26][27] Technology advances permitted sophisticated simulations with authentic and realistic learning experiences.[18]

In 2008, the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) changed the definition of Educational Technology to "the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources".[28][29]

2010 - 2020

[edit]Academic degrees focused on integrating technology, internet, and human–computer interaction with education gained momentum with the introduction of Learning Design and Technology (LDT) majors. Universities such as Bowling Green State University,[30] Pennsylvania State University,[31] Purdue,[32] San Diego State University,[33] Stanford, Harvard[34] University of Georgia,[35] California State University, Fullerton, and Carnegie Mellon University[36] have established undergraduate and graduate degrees in technology-centered methods of designing and delivering education.

Informal learning became an area of growing importance in instructional design, particularly in the workplace.[37][38] A 2014 study showed that formal training makes up only 4 percent of the 505 hours per year an average employee spends learning. It also found that the learning output of informal learning is equal to that of formal training.[38] As a result of this and other research, more emphasis was placed on creating knowledge bases and other supports for self-directed learning.[37]

Timeline

[edit]| Era | Media | Characteristics | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900s | Visual media | School museum as supplementary material (First school museum opened in St. Louis in 1905) | Materials are viewed as supplementary curriculum materials. District-wide media center is the modern equivalent. |

| 1914-1923 | Visual media films, Slides, Photographer | Visual Instruction Movement | The effect of visual instruction was limited because of teacher resistance to change, quality of the file and cost etc. |

| Mid 1920s to 1930s | Radio broadcasting, Sound recordings, Sound motion pictures | Radio Audiovisual Instruction movement | Education in large was not affected. |

| World War II | Training films, Overhead projector, Slide projector, Audio equipment, Simulators and training devices | Military and industry at this time had strong demand for training. | Growth of audio-visual instruction movement in school was slow, but audiovisual device were used extensively in military services and industry. |

| Post World War II | Communication medium | Suggested to consider all aspects of a communication process (influenced by communication theories). | This view point was first ignored, but eventually helped to expand the focus of the audiovisual movement. |

| 1950s to mid-1960s | Television | Growth of Instructional television | Instructional television was not adopted to a greater extent. |

| 1950s-1990s | Computer | Computer-assisted instruction (CAI) research started in the 1950s, became popular in the 1980s a few years after computers became available to general public. | The effect of CAI was rather small and the use of computer was far from innovative. |

| 1990s-2000s | Internet, Simulation | The internet offered opportunities to train many people long distances. Desktop simulation gave advent to levels of Interactive Multimedia Instruction (IMI). | Online training increased rapidly to the point where entire curriculums were given through web-based training. Simulations are valuable but expensive, with the highest level being used primarily by the military and medical community. |

| 2000s-2020s | Mobile Devices, Social Media | On-demand training moved to people's personal devices; social media allowed for collaborative learning. Smartphones allowed for real-time interactive feedback. | Personalized learning paths enhanced by artificial intelligence. Microlearning and gamification are widely adopted to deliver learning in the flow of work. Real-time data capture enables ongoing design and remediation. |

Models

[edit]ADDIE model

[edit]Perhaps the most common model used for creating instructional materials is the ADDIE Model. This acronym stands for the five phases contained in the model: Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate.

The ADDIE model was initially developed by Florida State University to explain "the processes involved in the formulation of an instructional systems development (ISD) program for military interservice training that will adequately train individuals to do a particular job, and which can also be applied to any interservice curriculum development activity."[39] The model originally contained several steps under its five original phases (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and [Evaluation and] Control),[39] whose completion was expected before movement to the next phase could occur. Over the years, the steps were revised and eventually the model itself became more dynamic and interactive than its original hierarchical rendition, until its most popular version appeared in the mid-80s, as we understand it today.

Connecting all phases of the model are external and reciprocal revision opportunities. As in the internal Evaluation phase, revisions should and can be made throughout the entire process.

Most of the current instructional design models are variations of the ADDIE model.[40]

Rapid prototyping

[edit]An adaptation of the ADDIE model, which is used sometimes, is a practice known as rapid prototyping.

Proponents suggest that through an iterative process the verification of the design documents saves time and money by catching problems while they are still easy to fix. This approach is not novel to the design of instruction, but appears in many design-related domains including software design, architecture, transportation planning, product development, message design, user experience design, etc.[40][41][42] In fact, some proponents of design prototyping assert that a sophisticated understanding of a problem is incomplete without creating and evaluating some type of prototype, regardless of the analysis rigor that may have been applied up front.[43] In other words, up-front analysis is rarely sufficient to allow one to confidently select an instructional model. For this reason many traditional methods of instructional design are beginning to be seen as incomplete, naive, and even counter-productive.[44]

However, some consider rapid prototyping to be a somewhat simplistic type of model. As this argument goes, at the heart of Instructional Design is the analysis phase. After you thoroughly conduct the analysis—you can then choose a model based on your findings. That is the area where most people get snagged—they simply do not do a thorough-enough analysis. (Part of Article By Chris Bressi on LinkedIn)

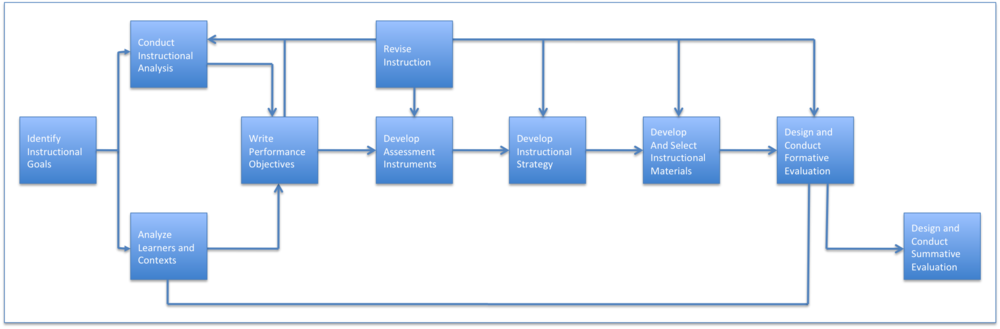

Dick and Carey

[edit]Another well-known instructional design model is the Dick and Carey Systems Approach Model.[45] The model was originally published in 1978 by Walter Dick and Lou Carey in their book entitled The Systematic Design of Instruction.

Dick and Carey made a significant contribution to the instructional design field by championing a systems view of instruction, in contrast to defining instruction as the sum of isolated parts. The model addresses instruction as an entire system, focusing on the interrelationship between context, content, learning and instruction.[46] According to Dick and Carey, "Components such as the instructor, learners, materials, instructional activities, delivery system, and learning and performance environments interact with each other and work together to bring about the desired student learning outcomes".[45] The components of the Systems Approach Model, also known as the Dick and Carey Model, are as follows:

- Identify Instructional Goal(s): A goal statement describes a skill, knowledge or attitude (SKA) that a learner will be expected to acquire

- Conduct Instructional Analysis: Identify what a learner must recall and identify what learner must be able to do to perform particular task

- Analyze Learners and Contexts: Identify general characteristics of the target audience, including prior skills, prior experience, and basic demographics; identify characteristics directly related to the skill to be taught; and perform analysis of the performance and learning settings.

- Write Performance Objectives: Objectives consists of a description of the behavior, the condition and criteria. The component of an objective that describes the criteria will be used to judge the learner's performance.

- Develop Assessment Instruments: Purpose of entry behavior testing, purpose of pretesting, purpose of post-testing, purpose of practice items/practice problems

- Develop Instructional Strategy: Pre-instructional activities, content presentation, Learner participation, assessment

- Develop and Select Instructional Materials

- Design and Conduct Formative Evaluation of Instruction: Designers try to identify areas of the instructional materials that need improvement.

- Revise Instruction: To identify poor test items and to identify poor instruction

- Design and Conduct Summative Evaluation

With this model, components are executed iteratively and in parallel, rather than linearly.[45]

Guaranteed Learning

[edit]The instructional design model, Guaranteed Learning, was formerly known as the Instructional Development Learning System (IDLS).[47] The model was originally published in 1970 by Peter J. Esseff, PhD and Mary Sullivan Esseff, PhD in their book entitled IDLS—Pro Trainer 1: How to Design, Develop, and Validate Instructional Materials.[48]

Peter (1968) & Mary (1972) Esseff both received their doctorates in Educational Technology from the Catholic University of America under the mentorship of Gabriel Ofiesh, a founding father of the Military Model mentioned above. Esseff and Esseff synthesized existing theories to develop their approach to systematic design, "Guaranteed Learning" aka "Instructional Development Learning System" (IDLS). In 2015, the Drs. Esseffs created an eLearning course to enable participants to take the GL course online under the direction of Esseff.

The components of the Guaranteed Learning Model are the following:

- Design a task analysis

- Develop criterion tests and performance measures

- Develop interactive instructional materials

- Validate the interactive instructional materials

- Create simulations or performance activities (Case Studies, Role Plays, and Demonstrations)

Other

[edit]Other useful instructional design models include: the Smith/Ragan Model,[49] the Morrison/Ross/Kemp Model[50] and the OAR Model of instructional design in higher education,[51] as well as, Wiggins' theory of backward design.

Learning theories also play an important role in the design of instructional materials. Theories such as behaviorism, constructivism, social learning, and cognitivism help shape and define the outcome of instructional materials.

Also see: Managing Learning in High Performance Organizations, by Ruth Stiehl and Barbara Bessey, from The Learning Organization, Corvallis, Oregon. ISBN 0-9637457-0-0.

Motivational design

[edit]Motivation is defined as an internal drive that activates behavior and gives it direction. The term motivation theory is concerned with the process that describes why and how human behavior is activated and directed. Motivation concepts include intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.

John M. Keller[52] has devoted his career to researching and understanding motivation in instructional systems. These decades of work constitute a major contribution to the instructional design field. First, by applying motivation theories systematically to design theory. Second, in developing a unique problem-solving process he calls the ARCS model.

Although Keller's ARCS model currently dominates instructional design with respect to learner motivation, in 2006 Hardré and Miller[53] proposed a need for a new design model that includes current research in human motivation, a comprehensive treatment of motivation, integrates various fields of psychology and provides designers the flexibility to be applied to a myriad of situations.

Hardré[54] proposes an alternate model for designers called the Motivating Opportunities Model or MOM. Hardré's model incorporates cognitive, needs, and affective theories as well as social elements of learning to address learner motivation. MOM has seven key components spelling the acronym 'SUCCESS' – Situational, Utilization, Competence, Content, Emotional, Social, and Systemic.[54]

Influential researchers and theorists

[edit]This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (December 2010) |

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, are these influential instructional designers, or anyone that influenced instructional design?. (February 2022) |

Alphabetic by last name

- Bloom, Benjamin – Taxonomies of the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains – 1950s

- Bransford, John D. – How People Learn: Bridging Research and Practice – 1990s

- Bruner, Jerome – Constructivism - 1950s-1990s

- Gagné, Robert M. – The Conditions of Learning has had a great influence on the discipline.[55]

- Gibbons, Andrew S - developed the Theory of Model Centered Instruction; a theory rooted in Cognitive Psychology.

- Heinich, Robert – Instructional Media and the new technologies of instruction 3rd ed. – Educational Technology – 1989

- Jonassen, David – problem-solving strategies – 1990s

- Kemp, Jerold E. – Created a cognitive learning design model - 1980s

- Mager, Robert F. – ABCD model for instructional objectives – 1962 - Criterion-Referenced Instruction and Learning Objectives

- Marzano, Robert J. - "Dimensions of Learning", Formative Assessment - 2000s

- Mayer, Richard E. - Multimedia Learning - 2000s

- Merrill, M. David – Component Display Theory / Knowledge Objects / First Principles of Instruction

- Osguthorpe, Russell T. – Overview of Instructional Design – The education of the heart: rediscovering the spiritual roots of learning[56]

- Papert, Seymour – Constructionism, LOGO – 1970s-1980s

- Piaget, Jean – Cognitive development – 1960s

- Reigeluth, Charles – Elaboration Theory, "Green Books" I, II, and III – 1990s–2010s

- Rita Richey - instructional design theory and research methods[57]

- Schank, Roger – Constructivist simulations – 1990s

- Simonson, Michael – Instructional Systems and Design via Distance Education – 1980s

- Skinner, B.F. – Radical Behaviorism, Programed Instruction - 1950s-1970s

- Vygotsky, Lev – Learning as a social activity – 1930s

- Wiley, David A. - influential work on open content, open educational resources, and informal online learning communities

See also

[edit]- Confidence-based learning – Learning system

- Design-based learning – Learner centric pedagogy

- E-learning (theory) – Cognitive science principles of effective multimedia learning

- Educational animation – Animations produced for the specific purpose of fostering learning

- Educational assessment – Educational evaluation method

- Educational psychology – Branch of psychology concerned with the scientific study of human learning

- Educational technology – Use of technology in education to improve learning and teaching

- Electronic portfolio – Collection of electronic evidence assembled and managed by a user

- Expertise reversal effect – reversal of the effectiveness of instructional techniques on learners with differing levels of prior knowledge

- Interdisciplinary teaching – Methods used to teach across curricular disciplines

- Instructional design coordinator – Process for design and development of learning resources

- Instructional theory – Theory that offers explicit guidance on how to better help people learn and develop

- Interaction design – Specialization of design focused on the experience users have of a product or service

- Learning object – in education and data management

- Learning sciences – Critical theory of learning

- Lesson study – Teaching improvement process

- M-learning – Distance education using mobile device technology

- Pedagogy – Theory and practice of education

- Storyboard – Use of graphics to plan a film or story

- Understanding by Design – Educational planning approach

- Universal Design for Learning – Educational framework

References

[edit]- ^ Merrill, M. D.; Drake, L.; Lacy, M. J.; Pratt, J. (1996). "Reclaiming instructional design" (PDF). Educational Technology. 36 (5): 5–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ^ Wagner, Ellen (2011). "Essay: In Search of the Secret Handshakes of ID" (PDF). The Journal of Applied Instructional Design. 1 (1): 33–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Ed Forest: Instructional Design Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Educational Technology

- ^ Mayer, Richard E (1992). "Cognition and instruction: Their historic meeting within educational psychology". Journal of Educational Psychology. 84 (4): 405–412. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.405.

- ^ Duffy, T. M., & Cunningham, D. J. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the design and delivery of instruction. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan

- ^ Duffy, T. M., & Jonassen, D. H. (1992). Constructivism: New implications for instructional technology. In T. Duffy & D. Jonassen (Eds.), Constructivism and the technology of instruction (pp. 1-16). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ Tennyson, Robert; Dijkstra, S.; Schott, Frank; Seel, Norbert (1997). Instructional Design: International Perspectives. Theory, research, and models. Vol. 1. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. p. 42. ISBN 0805814000.

- ^ Silber, Kenneth; Foshay, Wellesley (2010). Handbook of Improving Performance in the Workplace, Instructional Design and Training Delivery. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. p. 62. ISBN 9780470190685.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Reiser, R. A., & Dempsey, J. V. (2012). Trends and issues in instructional design and technology. Boston: Pearson.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, B. (2009). The history of instructional design and technology. Archived 2012-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thalheimer, Will. People remember 10%, 20%...Oh Really? October 8, 2006. "Will at Work Learning: People remember 10%, 20%...Oh Really?". Archived from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ^ Briggs, Leslie; Gustafson, Kent; Tillman, Murray (1991). Instructional Design: Principles and Applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. p. 375. ISBN 9780877782308.

- ^ Bloom's Taxonomy. Retrieved from Wikipedia on April 18, 2012 at Bloom's Taxonomy

- ^ Instructional Design Theories Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine. Instructionaldesign.org. Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ a b c d Reiser, R. A. (2001). "A History of Instructional Design and Technology: Part II: A History of Instructional Design Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine". ETR&D, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2001, pp. 57–67.

- ^ a b History of instructional media. Uploaded to YouTube by crozitis on Jan 17, 2010. Retrieved from "History of Instructional Media". YouTube. 17 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ^ a b A hypertext history of instructional design Archived 2012-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 11, 2012

- ^ a b c Markham, R. "History of instructional design Archived 2013-02-28 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved on April 11, 2012

- ^ a b History and timeline of instructional design Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 11, 2012

- ^ Conole G., and Fill K., "A learning design toolkit to create pedagogically effective learning activities". Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2005 (08).

- ^ Carr-Chellman A. and Duchastel P., "The ideal online course," British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 229–241, July 2000.

- ^ Koper R., "Current Research in Learning Design," Educational Technology & Society, 9 (1), 13–22, 2006.

- ^ Britain S., "A Review of Learning Design: Concept, Specifications and Tools" A report for the JISC E-learning Pedagogy Programme, May 2004.

- ^ IMS Learning Design webpage Archived 2006-08-23 at the Wayback Machine. Imsglobal.org. Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ Braine, B., (2010). "Historical Evolution of Instructional Design & Technology". Retrieved on April 11, 2012 from "TimeRime.com - Historical Evolution of Instructional Design & Technology timeline". Archived from the original on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ Webbees. "Xterior - Windschermen, Windschermen". www.xterior-windschermen.nl. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ^ Trentin G. (2001). Designing Online Courses. In C.D. Maddux & D. LaMont Johnson (Eds) The Web in Higher Education: Assessing the Impact and Fulfilling the Potential Archived 2014-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 47-66, The Haworth Press Inc., New York, London, Oxford, ISBN 0-7890-1706-7.

- ^ Association for Educational Communications and Technology (2008). Definition. In A. Januszewski and M. Molenda (Eds.), Educational Technology: A definition with commentary. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Hlynka, Denis; Jacobsen, Michele (2009). "What is educational technology, anyway? A commentary on the new AECT definition of the field". Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology. 35 (2). ISSN 1499-6685. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04.

- ^ "Learning Design and Technology". Archived from the original on 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2016-08-03. BGSU LDT

- ^ "Learning, Design, and Technology Program — Penn State College of Education". Archived from the original on 2016-07-23. Retrieved 2016-08-03. Penn State LDT

- ^ "Master's in Learning Design and Technology | Purdue Online". Archived from the original on 2016-08-03. Retrieved 2016-08-03. Purdue LDT

- ^ "Journalism and Media Studies". Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2016-08-03. SDSU LDT

- ^ "Learning Design and Technology (LDT)". 5 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-03. Stanford LDT

- ^ "MEd in Learning, Design, and Technology - University of Georgia College of Education". Archived from the original on 2016-09-01. Retrieved 2016-08-03. UGA LDT

- ^ "METALS – Master of Educational Technology and Applied Learning Science @ Carnegie Mellon". metals.hcii.cmu.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-04-01.

- ^ a b "Instructional Design and Technical Writing". Cyril Anderson's Learning and Performance Support Blog. 2014-05-05. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ a b "Informal learning is more important than formal learning – moving forward with 70:20:10 - 70:20:10 Institute". 70:20:10 Institute. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ a b Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development. (5 vols.) (TRADOC Pam 350-30 NAVEDTRA 106A). Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, August 1975. (NTIS No. ADA 019 486 through ADA 019 490).

- ^ a b Piskurich, G.M. (2006). Rapid Instructional Design: Learning ID fast and right.

- ^ Saettler, P. (1990). The evolution of American educational technology.

- ^ Stolovitch, H.D., & Keeps, E. (1999). Handbook of human performance technology.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2005). The ten faces of innovation: IDEO's strategies for beating the devil's advocate & driving creativity throughout your organization. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ Hokanson, B., & Miller, C. (2009). Role-based design: A contemporary framework for innovation and creativity in instructional design. Educational Technology, 49(2), 21–28.

- ^ a b c Dick, Walter; Carey, Lou; Carey, James O. (2005) [1978]. The Systematic Design of Instruction (6th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. pp. 1–12. ISBN 0-205-41274-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ed Forest (23 November 2015). "Dick and Carey Instructional Model". Archived from the original on 2015-11-24.

- ^ Esseff, Peter J.; Esseff, Mary Sullivan (1998) [1970]. Instructional Development Learning System (IDLS) (8th ed.). ESF Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 1-58283-037-1. Archived from the original on 2008-11-19.

- ^ ESF, Inc. – Train-the-Trainer – ESF ProTrainer Materials – 813.814.1192 Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine. ESF-ProTrainer.com (2007-11-06). Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ Smith, P. L. & Ragan, T. J. (2004). Instructional design (3rd Ed.). Danvers, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2001). Designing effective instruction, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley.

- ^ Joeckel, G., Jeon, T., Gardner, J. (2010). Instructional Challenges In Higher Education: Online Courses Delivered Through A Learning Management System By Subject Matter Experts. In Song, H. (Ed.) Distance Learning Technology, Current Instruction, and the Future of Education: Applications of Today, Practices of Tomorrow. (link to article Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Keller, John. "arcsmodel.com". John M. Keller. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Hardré, Patricia; Miller, Raymond B. (2006). "Toward a current, comprehensive, integrative, and flexible model of motivation for instructional design". Performance Improvement Quarterly. 19 (3).

- ^ a b Hardré, Patricia (2009). "The motivating opportunities model for Performance SUCCESS: Design, Development, and Instructional Implications". Performance Improvement Quarterly. 22 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1002/piq.20043.

- ^ Dick, Walter; Carey, Lou; Carey, James O. (17 March 2014). The Systematic Design of Instruction (8 ed.). Pearson. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Osguthorpe, Russell T. (1996-09-01). The education of the heart: rediscovering the spiritual roots of learning. Covenant Communications. ISBN 9781555039851. Archived from the original on 2017-02-07.

- ^ Richey, Rita C.; Klein, James D. (2014). Design and Development Research: Methods, Strategies, and Issues. doi:10.4324/9780203826034. ISBN 9780203826034.

External links

[edit]- Instructional Design – An overview of Instructional Design

- ISD Handbook

- Edutech wiki: Instructional design model

- ATD: What Is Instructional Design?